Empire of Hype: A History of Artists and the Media [Article]

Visual Arts Journal - January 29, 2016

Empire of Hype: A History of Artists and the Media

Early modern artistic production and distribution were not conducive to the participation of intermediaries such as the press. Patronage through official, government/aristocratic channels, and vetting by the comparably elitist academy exercised tight control over the domain of art, making it inhospitable to those deemed outsiders or otherwise unworthy. With the emergence of modern art, however, artists themselves–many from social classes typically excluded before–began to subvert the institutional traditions that had long determined who could be an artist and what art was acceptable.

The media became a factor in the production and selling of art, and artists began to use the press for their own devices, as a means of promotion and communication. The media eventually came to exert a powerful influence on art, not just as a publicty vehicle for artists, but as a major force in shaping the public’s perception of art and establishing the careers/identities, even the historical record of many artists. Arguably, the media–certain elements, at least–were partly responsible for the rise of modern art, rather than a reactive force that simply responded to developments that were initiated well out of their reach.

The Libellistes

One of the earliest instances of media involvement with art took place with the libellistes, a group of covert pamphlet writers in 18th-century France. The libellistes sprung from the ranks of unemployed writers and “low-born” intellectuals. They were reacting to the rigidity of the art establishment, particularly the Academy of Painting and Sculpture and its official salon exhibitions, which epitomized the centralizaton of culture and sanctioning of art in France. The libellistes’ pamphlets signalled the emergence of an alternative art media, deviating from the “party line” and opposing the status quo. They were arguably among the first true art critics.

Their highly satirical pamphlets often employed visual caricatures to parody the sanctioned art. To disseminate their viewpoint more widely, men were hired to read aloud from these pamphlets, in the streets and public squares, for the benefit of the illiterate. The pamphlet trade launched an unprecedented channel of transmission between the high and low cultures–literally between the academy and the street–at a time when such demarcations were extremely rigid.

The Impressionists

The tradition represented by the libellistes–that of alternative art world voices–intensified in the following century, and artists began to exert more influence on their own careers. In mid-19th-century Europe, entrenched arbiters of public taste such as the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in France still held sway, and successful artists were only those sanctioned by these institutions. The Salon des Beaux-Arts was a major national showcase that could make or break artistic careers. If rejected from these exhibitions, paintings were returned stamped “R” (for “refuse”)–a major stigma that destroyed the career of many a promising artist.

In response to the rigidity of the art establishment, Impressionist painter Eduard Manet organized, in 1863, the legendary Salon de Refusé, an exhibition of painters rejected from the salon. This alternative exhibition was an early example of artists moving outside of established channels to show work that was innovative and disinclined to pander to mainstream public taste. Because they were making an organized break from convention, Manet and his cohorts diligently cultivated champions in the press in order to reach the public and other artists.

Dadaists and Surrealists

The Dadaists and Surrealists were among the first artists to actively, programmatically enlist the mass media as confederates in their efforts to promote their work and further their then-radical goals. Surrealism in particular had an unprecedented affinity with the media because it was more than a mere genre, but rather a self-conscious political art movement and school of thought whose primary focus was the territory of the unconscious. The manifestoes and public events that were a part of Surrealism required a popular forum to promote them, and the artists and theorists of the movement were not hesitant to rely on the press. The Surrealists also created their own media to further the cause of their art, turning out an endless stream of journals, magazines and other publications.

The Dadaists and Surrealists understood the power of spectacle and scandal better than any artistic movement before them, and actually incorporated these elements into their work. In some cases, the press became necessary collaborators in helping them fully realize disembodied or “dematerialized” conceptual works–art lacking concrete dimensions–like the intentional disruption of public events, for which they were notorious. Such works, without a media forum, could not truly exist beyond the moment they occurred.

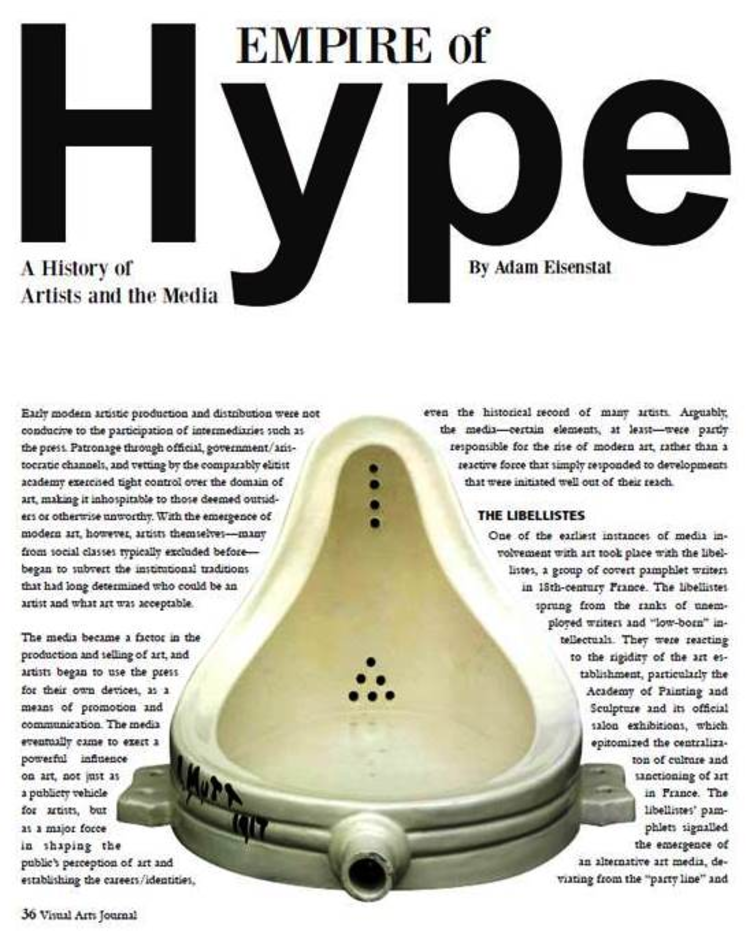

Surrealist tricksters like Salvador Dali, and his contemporary Marcel Duchamp (who wasn’t formally assocated with the movement), used calculated outrage and aggressive self-promotion to subvert bourgeois mores and chip away at the foundations of art. Duchamp, for example, scandalized the art world and polite society when he exhibited an ordinary men’s room urinal (signed “R. Mutt”) and called it art (see figure). This exemplified his concept of the “readymade,” which called into question fundamental definitions of art. The press, in disseminating news of such antics, was instrumental in establishing the Surrealists‘ powerful mythology, which was an essential feature of this movement whose aims went beyond the creation of pleasing artifacts.

Jackson Pollock

The postwar dominance of Abstract Expressionism and the emergence of New York City as the center of the international art world paralleled the rise of American prosperity and the country’s establishment as a global power. A major element in this prosperity was the growth of mass media and consumerism, fueled by ubiquitous and increasingly sophisticated marketing techniques.

At the same time, among artists and bohemians there developed an ingrained hostility toward these commercial forces, which were seen as corrupters and trivializers of artistic purity. An undercurrent to the Abstract Expressionist movement was the belief that art was a bastion standing against what the artists saw as spiritual decay spawned by postwar prosperity and the rise of a media-dominated society. The degree of the artists’ adversarial stance is sometimes exaggerated, and artists like Willem de Kooning were eager to expound on the pleasures of vulgarity, but Abstract Expressionist art itself would seem to confirm this ideology. The art was driven by a purity of form, a profound affirmation of the artistic life, and the sanctity of the creative vision–in sharp contrast to the banality of mass culture.

Jackson Pollock, the artist perhaps most famously associated with Abstract Expressionism, was thrust into the spotlight and made a star by the very mechanism to which he was–at least artistically–in opposition. Pollock was hardly the sort of media-savvy self-promoter we associate with today’s art world player. He was not especially articulate and had a bent for the sort of alcohol-fueled bad behavior that undermines the deft careerism characteristic of marketing-pro artists. Yet, the media’s importance in his career and in his mythology is undeniable. An article in Life magazine in 1949, generously illustrated with his work, introduced Pollock to America as something akin to the Marlon Brando of abstract art. The article catapulted him to center stage of the American art world.

Another fateful art/media confluence in Pollock’s life was the film another artist, Hans Namuth, made of him at work, capturing his camera-friendly “action painting” technique. This further mediation, or–as Pollock might have thought–sullying of his power as a force of nature, may have sent him over the edge. He immediately began drinking again after an extraordinarily productive two-year period of sobriety, and not long afterward killed himself and a passenger in a car wreck.

The paradox here is that Pollock was the first American art superstar, yet he was fundamentally incapable of deflecting the glare caused by that stardom. His life, as a function of his relationship with the media, is a tragedy of Greek proportions–a classic artistic-bohemian myth whereby commerce and its handmaidens, marketing and PR, subvert the artist’s identity and destroy him.

After Pollock, no one could deny the power of the media to not only promote art and get an artist’s work “out there,” but also as an engine of mythology, a means of creating and defining an artist as an agglomeration of his work, life, and personality–his entire being.

It would no longer be possible for an artist–save the most naive or unsophisticated–to claim with any ingenuousness that “It’s all about the work.” From that time forward it’s been all about everything. Pollock’s success and his deification resulted from not only his work, but also his refraction through the prism of the media. Consequently, he inhabits a curious position in art history as perhaps the last pure modernist, but also the progenitor of postmodernism, which is characterized by the artist’s awareness of his or her presentation, and the intertwining of creation and promotion.

Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol was the anti-Pollock. He integrated commerce and media deeply into the fabric of his art–soup cans, tabloid photos, movie stills–blurring any distinctions among them. The mass media were wholly complicit in his rise, as his coterie of “superstars” and real celebrities provided the press with a steady stream of good copy and photo ops, which it eagerly disseminated. The media embraced Warhol and he in turn embraced the media. His persona and work saturated not only the precincts of art, but also the more vulgar realm of mass culture. Examples of this abound, such as his own magazine, Interview, a gossipy public record of the demimonde he cultivated; and such whimsical acts of reflexivity as playing himself on The Love Boat.

Warhol, as a pop artist, drew from the media and commercial culture–the external world–for his imagery (he possessed his art); Pollock’s art reflected his tumultuous internal world (his art possessed him). They were very different types of artists, which is clear not just from the art itself, but in the dialectical relationship each one had with the media: the media fed off Pollock (it consumed him and he lost control); while Warhol fed off the media (he digested it and maintained control).

Warhol, who was heavily influenced by Duchamp, opened the floodgates for legions of artists who gleefully embraced the media as both a source of inspiration and a vehicle for self-promotion. Some of the most successful, like Julian Schnabel, Jeff Koons and, more recently, Damien Hirst, have achieved fame and fortune in large part because of their ability to use the media to craft their mystique–that amorphous alloy of charisma, mystery, and unconventionality–while not necessarily appearing to do so.

The division today between art and media is far less distinct than in past eras. At one time art and media existed in separate domains. If they connected at all, it was little more than a temporary alliance of convenience. For artists today, at any level, escape from the influence of media seems impossible, and the potential rewards it promises are exceedingly hard to resist.